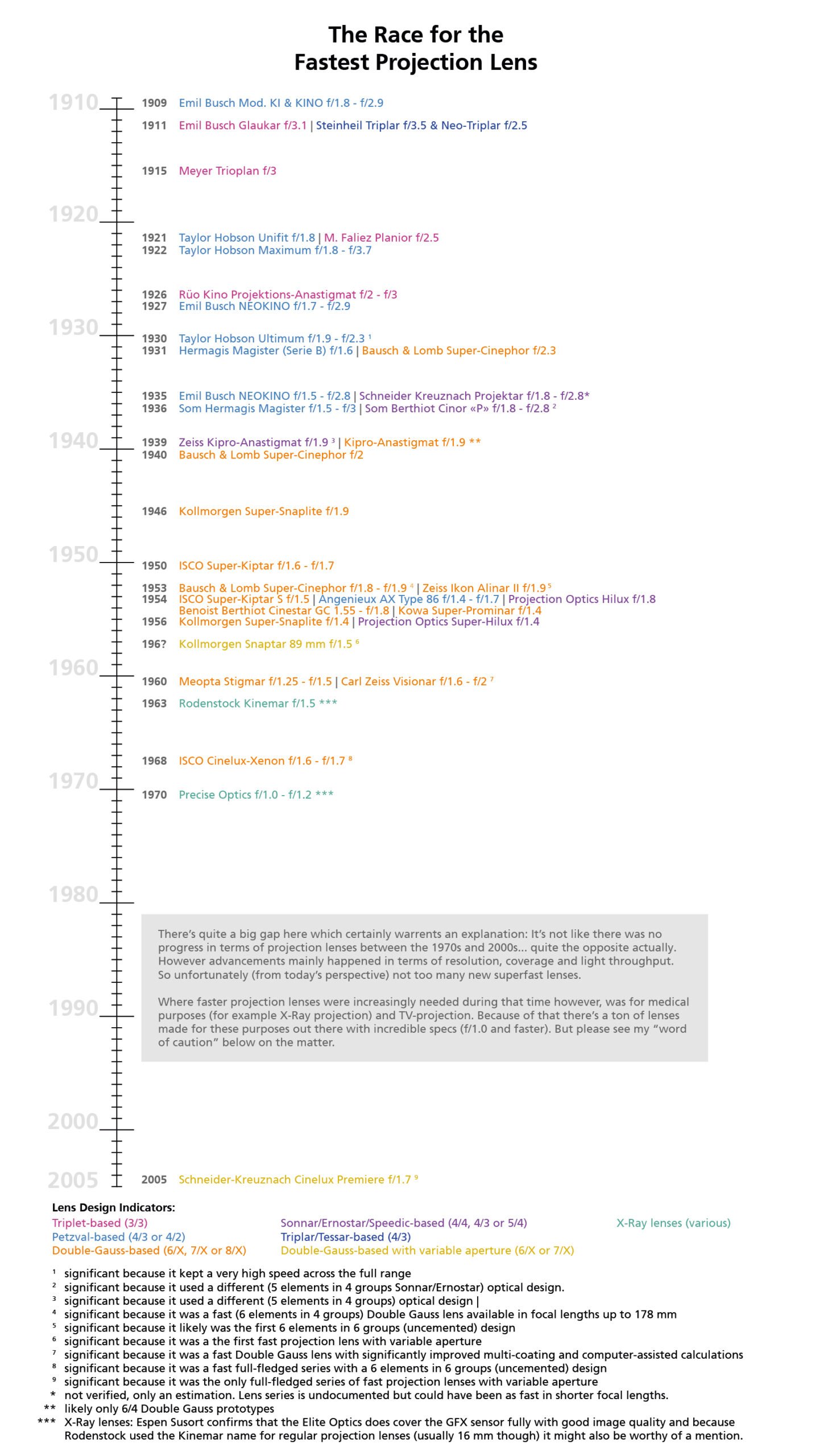

Press material of the time depicted the early history of cine projection as the quest for speed: vivid brilliance on screen meant healthy box office – making the business of brute-force light transmission a priority. Bigger audiences meant bigger cinemas, bigger screens, and therefore even greater demand on projection lenses. The race to improve the quantity of light through the lens spanned continents and centuries, gradually maturing into an appreciation of the quality of resolution and coverage.

Advertising aside, source material charting the evolution of these lenses is thin on the ground, and modern shooters wanting to use them as taking lenses may experience the discomfort and/or thrill of wandering into uncharted territory. Complicating factors include.

- The lack of reliable inscriptions/indicators of speed. Despite the volume of media claims, the lenses themselves (especially early examples) were often silent re: their transmissivity – commonly featuring a barrel diameter but not the f-value. This was more a function of accuracy than modesty: a lens series might, for instance, be designated f2 but span focal lengths from 3″ to 6″ in quarter-inch increments, with the same size front and rear element – obviously they weren’t all f2, but ± tenths of a stop. Between 1920 and 1960 great strides were made in coatings technology – allowing makers to eke out stop-fractions of light from this year’s ‘new and improved’ model, which was often described in terms such as ‘10% better’ than the outgoing range (despite being outwardly identical), without pinning an aperture value on each lens for public consumption. In uncommon cases – such as Dallmeyer – we have access to original factory worksheets that provide exact specifications (eg 75mm / f1.947).

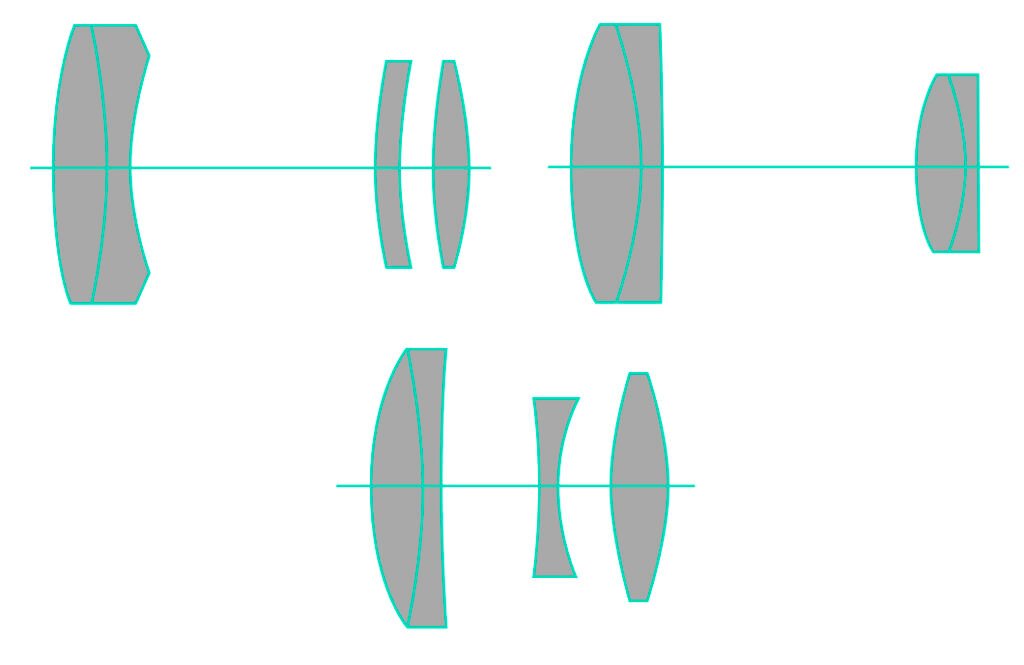

- Different lens schemes. Petzval-type designs offered relatively ‘high speeds’ from the get-go, and were improved over time, but were relatively poorly corrected. Sonnar/Speedic types were often only supplied in a limited range of focal lengths and Double Gauss lenses as well, though only in the beginning. We also find one-off and prototype lenses with unusual schemes on the market, unconnected to volume-produced ranges, which are hard to compare or not relevant for most people.

- Different projection formats. Lenses are often sold without projectors, cutting them adrift from their original application, which may once have been the projection of 8, 9.5, 16, 35 or 70mm film – with corresponding image circles. As a general guide, all 70mm cine projector lenses cover GFX and smaller formats, and all 35mm cine projector lenses cover 35mm and smaller formats. Among 16mm projection lenses, many lenses above 60 mm ‘cover full frame’ in terms of illumination, but rarely aberration – depending on the focal flange distance and whether infinity focus is needed. For more on this topic, see here >. Most 16mm projection lenses above 35 mm cover APS-C , but 8mm and 9.5mm projection lenses are only suitable for M43 – and not all of those. However, because 35mm projection lenses best suit adaptation to all modern cameras, it was chosen as the threshold for this overview.

While soap-powder manufacturers competed on the pages of glossy magazines for ever-more-blindingly whiter-than-white whites, lens-makers vied (somewhat creatively) for the title of ‘world’s fastest projection lens’. Eg . . .

Here’s a chronological overview of the most notable lens series created during the long-lasting competition for the fastest projection lens in the world . . . .

The Petzval/Triplar/Tessar-Class

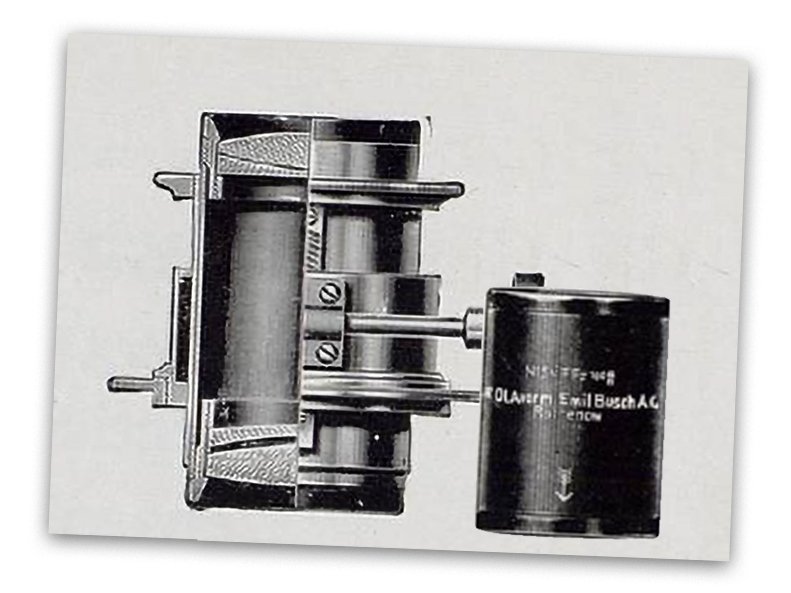

Emil Busch from Germany was one of the first companies to offer lenses of that kind for projection purposes. There were earlier samples, but a series called KI & KINO (german word for CINEMA) marks the starting point of what I would consider a willful attempt at creating a significantly faster lens. It first appeared around 1909 and while no specific f-stops were supplied for projection lenses at the time, the fastest lenses among those Petzval-based lenses likely boasted a speed of f/1.8, which is quite impressive not even a decade into the new century, particularly because many of them were in the telephoto range focal-length wise.

The UK-made Dallmeyer Cinematograph lenses of the time were also fast, but started at f/2 . . .

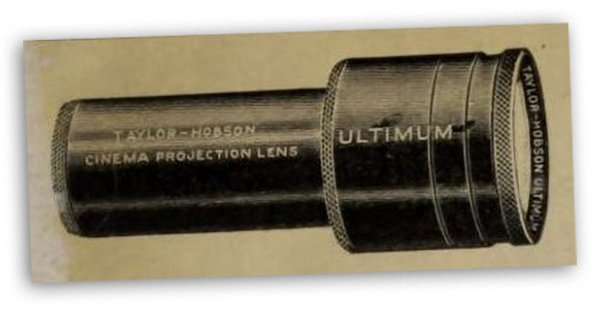

Circa 1921/1922, Taylor Hobson released the Maximum series of projection lenses in speeds up to f/1.8 – (probably) slighly faster than the Busch KINO lense, at least in longer focal lengths around 150-180 mm. The Maximum also was the first lens of its kind with a 4 elements in 2 groups Petzval variant and for a considerable amount of time also the fastest.

Circa 1930, the company released the Ultimum line – no longer limited to 52.5mm diameter and using a stepped design (similar to the Emil Busch Neokino) with significantly bigger front diameters, enabling them to make very fast long lenses (for example an 127/1.9 while even the fastest comparable Neokino lens was likely still at f/2.2)

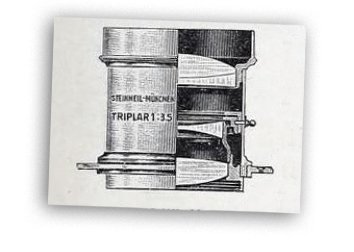

One notable exception to the regular Petzval schemes might be the Steinheil Triplar. It used a 4 elements in 3 groups Tessar-like design, though significantly earlier and also faster… wait, what? Yes, indeed, Steinheil invented a Tessar-like design (just reversed) in 1881 and even patented it. It wasn’t completely novel – really a derivative of the shorter and often forgotten second design by the Hungarian genius Petzval, later dubbed Orthoskop. It was originally intended as a landscape lens and thus slower than the Petzval Portrait lens. Adolph Steinheil developed his own version of the Orthoskop, was granted a patent in 1881 and called it Portrait Antiplanet after it was released.

Because of its similarity to the famous Zeiss Tessar, I’ve been interested if it is significantly different in terms of its optical properties. Thanks to Bill Claff – creator of the optical bench at photons to photos – who recreated the models in his software, it became clear that this lens wasn’t close to the Tessar, particularly in terms of angle of view, but likely in other aspects as well and certainly also in terms of glass-types used.

Around 1911 the Triplar was sold as a projection lens on Liesegang cine projectors. While slower than the regular Petzval projection lenses of its time, some variants of it (Neo-Triplar) were f/2.5, which compared well to Triplets like the f/3.1 Glaukar or similar lenses, which it likely rivaled in terms of image quality.

We don’t know the exact parameters of this lens, but it seems like Steinheil put some thought into the lens in terms of correction:

Steinheil again pioneered the field by inventing his Antiplanet in 1881. This objective presents a completely new construction principle. Instead of previously, e.g. in the aplanats, each half was corrected separately, then combined into one objective, Steinheil this time wanted to produce an objective whose halves were equally but oppositely defective, so that the defects had to cancel each other out when the halves were combined into the same objective. The front half had a converging effect and the rear half a dispersing one, so that the latter could not produce an image.

(Valokuvaajan Valo-Oppi by H.Schmidt-E.Piirinen, 1920)

While only tangentially related to the topic at hand it’s still fascinating to see that the 4-3 Triplar design was produced in speeds as fast as f/3.8 in focal lengths up to 300 mm in 1911 already.

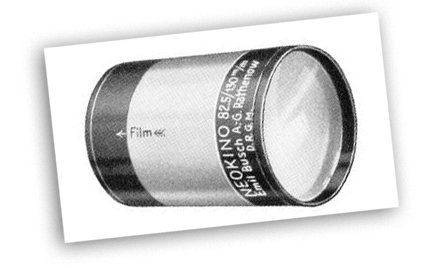

In 1927 it was once again Emil Busch, who pioneered a new series of Petzval projection lenses: Neokino. These lenses reached a speed of f/1.7 in shorter focal lengths.

In 1931 Hermagis from France took the next step, offering their Magister Serie B in speeds up to f/1.6.

During 1935 and 1936 Emil Busch released their improved and faster Neokino series and Som Berthiot (who seems to have acquired Hermagis) also offered the Magister series in speeds up to f/1.5. At the same time new – in some respects superior – types of lens designs, like 4-6 elements Anastigmats derived from extended Triplet designs as well as Double-Gauss based constructions were on the rise (see below).

Regardless of the waning importance (at least for shorter focal lengths) of this already ancient optical design, Angeniéux took one last big swing and created the fastest Petzval projection lens in 1954: the AX Type 86 with a speed of f/1.4 in some focal lengths.

The Triplet/Sonnar/Speedic-Class

Lenses in this category share a derivation from the classic Taylor Triplet. While the story of the Triplet in projection certainly started earlier (lantern lenses etc.) the first notably fast and high-quality lens of its kind used for projection might have been the Emil Busch Glaukar with a speed of f/3.1 in 1911. It would have been possible (but technically much harder) to make the shorter lenses even faster, but the company chose to prioritise consistent quality.

These lenses had a long lifespan and were highly praised, but the Petzvals were much more popular – not least because they were less than half the price of the Glaukar in 1912.

Meyer offered their well-known Trioplan at a similar speed of f/3 as well around 1915. It seems like their Kinon lenses featuring a classic Petzval construction were more commonly used for projection however, which isn’t surprising because the Trioplan was primarily advertised as a cine taking lens, before the significantly faster Kino-Plasmat inherited its place. During this period, it was common for symmetrical lenses to be advertised as suitable for taking, enlargement and projection – as indeed they remain today.

In 1921 M. Faliez from France showed their Planior lens series, which was even faster than the at f/2.5.

In 1926 Rüo Optik from Germany offered their Kino Projektions-Anastigmat – also a simple Triplet – in speeds up to f/2.

From this point on, however, newly developed (or recently improved) 4- and 5-element Triplet derivatives took over.

The first notable example for 35mm projection may have been the 1935 Schneider Kreuznach Projektar. There’s no documentation on the lens besides some patent filings, but it’s possible that the fastest lenses of that series had a speed of f/1.8. It used a unique design of four elements in three groups (distantly related to Sonnar/Speedic) which was simultaneously developed by SOM Berthiot.

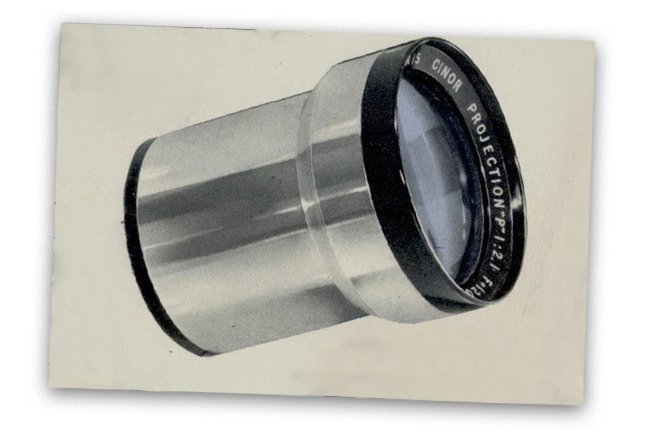

One year later in 1936 Som Berthiot offered their Cinor “P” series, a different 5-element Sonnar/Speedic variant, likely with a bigger range of focal lengths starting at a speed of f/1.8. It was popular but the longer focal lengths (above 90 mm) were somewhat slower at f/2.1 – f/2.8.

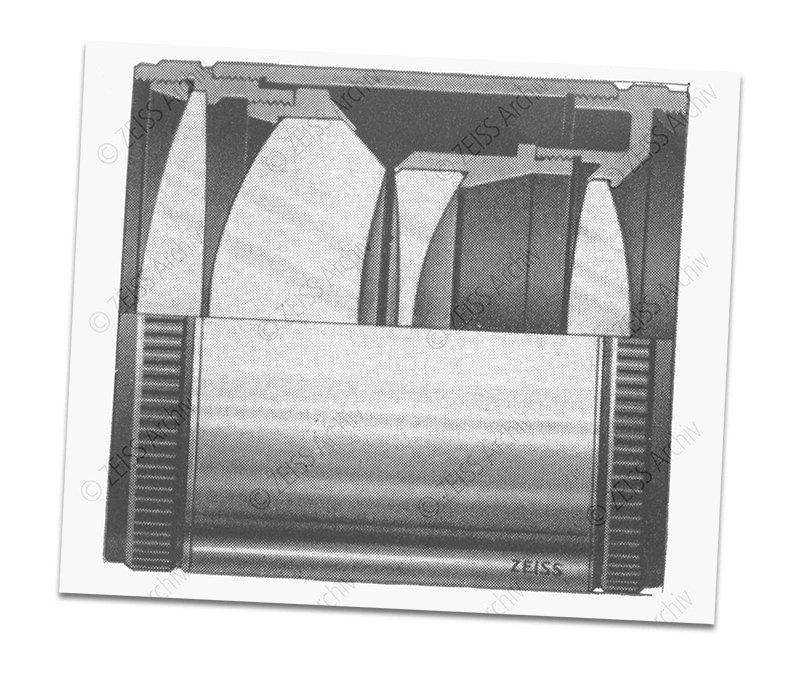

While not quite as fast (at f/1.9) the 1939 Zeiss Kipro-Anastigmat offered consistent speed across the full range of focal lengths, better correction and likely also improved sharpness. It’s unclear when the Zeiss Ikon Ernostar lenses (also produced in speeds up to f/1.8) were released and how they compared to the former Zeiss lenses or their competition from France. It’s likely though that they appeared significantly later than the Kipro-Anastigmats.

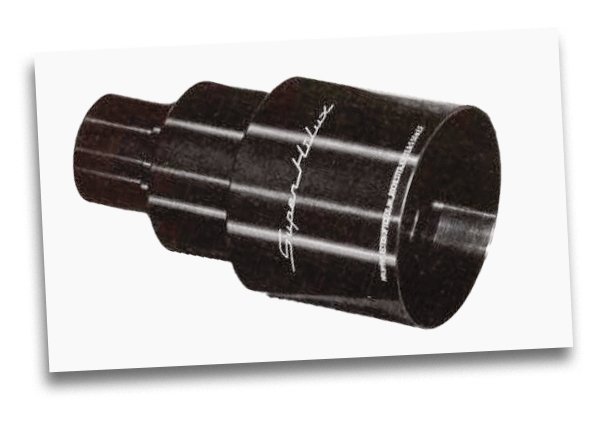

In 1954 Projection Optics from the US offered a full range of 4-element Sonnar-type lenses – the Hilux with a consistent speed of f/1.8 across big parts (51-107 mm) the full range.

In 1956 it was replaced by the Super-Hilux. While the initial version might have been similar to its predecessor in terms of speed, it got an updated version soon after, reaching a speed of f/1.4. For more on this small but inventive Rochester maker, please see The Projection Optics Story >.

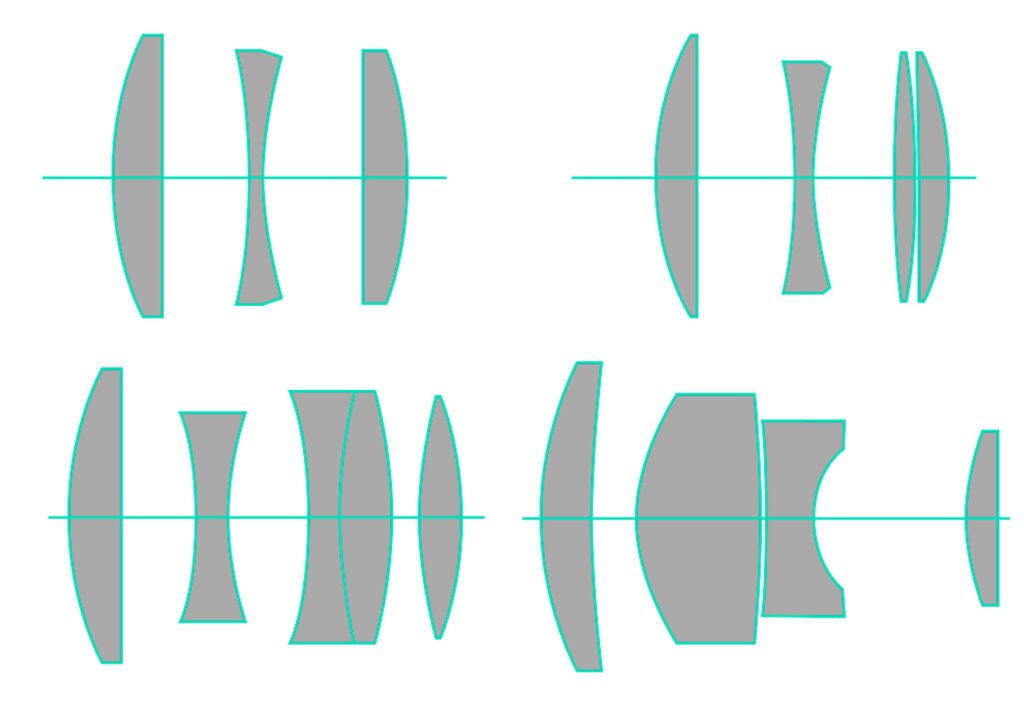

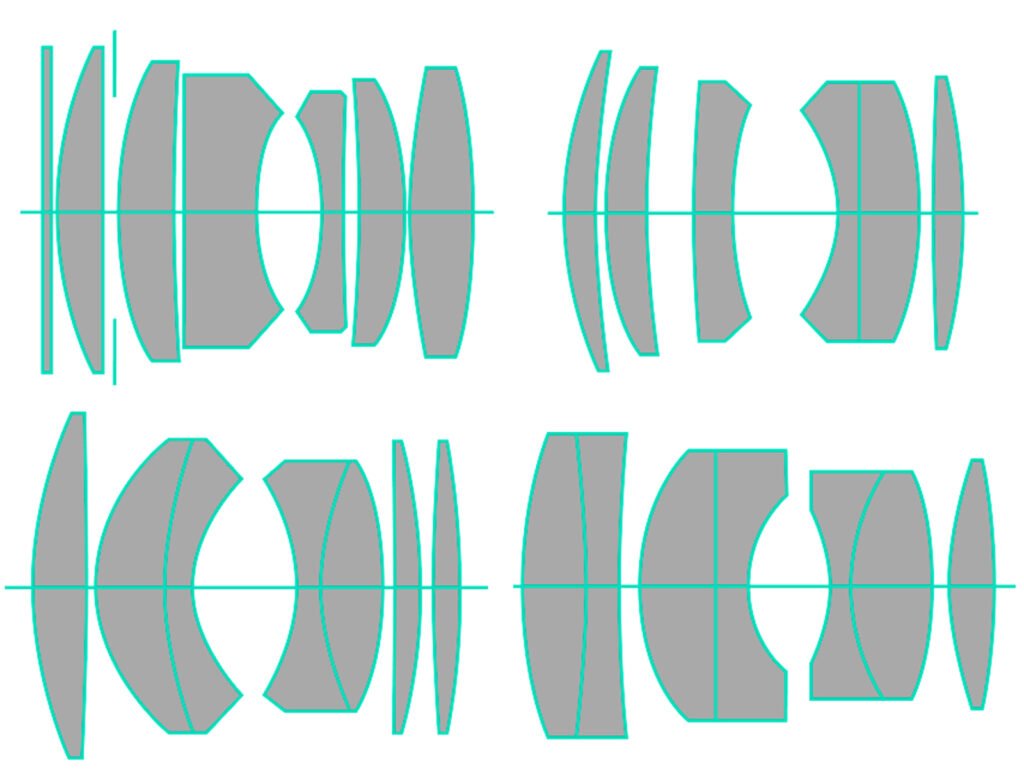

Double-Gauss Variants

Double-Gauss variants, typically comprising six or seven cemented and uncemented elements, can be considered the culmination of the need for speed in projection lenses.

The first notable example was the Bausch & Lomb Super-Cinephor in 1931. While its speed had to be be reduced to f/2.3 on paper (compared to already existing Petzval Cinephor lenses with an aperture of f/2) it was already able to gather more light due to its construction and new improved materials.

Zeiss seems to have experimented with a 6-element version of their Kipro-Anastigmat around 1939 with a speed of f/1.9. No more details are currently known, however, and it’s possible that this version never went into full production and remained a prototype.

In 1940 Bausch & Lomb offered their improved Super-Cinephor however, finally catching up to the f/2 of their Petzval lines with vastly improved image quality across the frame.

It took their competitor Kollmorgen several more years before they were able to release their Super-Snaplite series which was even faster at f/1.9.

The exact dates of the early ISCO – a subsidiary of Schneider Kreuznach from Germany – production is still somewhat nebulous, but somewhere around 1950 the first models of their faster Super-Kiptar line of lenses with speeds up to f/1.6 were released to great success all around the world, though likely first in Europe and later in the US. The lens was offered in a wide range of focal lengths and even longer ones were no slower than f/1.7. For lots more information about the Super-Kiptar and several other lens series by ISCO, please out The Kiptar Story >.

Bausch & Lomb didn’t attempt to rival the Super-Kiptar in terms of speed with their 1953 upgrade of the Super-Cinephor to f/1.8, but instead opted for consistency and range, extending the focal lengths up to 200+ mm with a speed of f/1.9 still.

In the same year Zeiss Ikon started to offer the Alinar II. It wasn’t as fast and also only available in a slightly limited range of focal lengths, but it marked the first completely uncemented design with six elements in six groups, making it better prepared for the newly arising challenges of vastly more powerful lamps by not being as prone to burn damage.

In 1954 – the culmination of the fastest projection lens race – ISCO released their Super-Kiptar S series with a speed of f/1.5. The incredibly fast Angenièux AX Type 86 (mentioned under the Petzval race) was of course completely different.

There was another series with a similar design however, which might have been around in France, the Benoist Berthiot Cinestar GC line at f/1.55. Unfortunately we don’t know the exact release date.

Another competitor then appeared: the Japanese Kowa Super-Prominar series with a speed of f/1.4. While that speed applied to a handful of lenses between 65 and 75 mm, it’s impressive nontheless. The full range isn’t well documented but by 1974 Super-Prominar was offered in focal lengths from 123 to 146 mm with a speed of f/1.6 and thus it’s safe to assume additional focal lengths in between were also manufactured.

Two years later in 1956 Kollmorgen advertised an f/1.4 version of their now rare Super-Snaplite.

The similarly rare Snaptar f/1.5 may be a version with variable aperture – likely also released at that time.

After that the race seems to have been halted for a while, but in 1960 Meopta from Czechoslovakia/USSR started producing its Stigmar range. The shortest of them, with an incredible speed of f/1.25, had a unique eight-element scheme. In the same year Carl Zeiss unveiled their new Visionar series, which – while not quite as fast – was yet another uncemented six-elements series with f/1.6 lenses up to 100 mm and very long focal lengths, still having a speed of f/1.9. Online the Visionar is sometimes referred to as the first lens series to have benefitted from computer-optimized calculation, but because I couldn’t find a reference for that yet, I’d still file this as speculation.

In 1968, almost two decades after its initial launch, ISCO released Super-Kiptar’s successor: the Cinelux-Xenon family. While still based on a classic 6 elements in 4 groups design, these lenses were among the first fast projection lenses, reportedly created with computer-assisted calculation and multicoating.

Unfortunately they were not produced in significant numbers, so they’re somewhat scarce today. While all of the other lenses of the time sacrificed speed in order to provide a more even performance aimed at the new formats emerging, the Cinelux-Xenon with its speed of f/1.6 to f/1.7 remained the only lens at this level for almost thirty years.

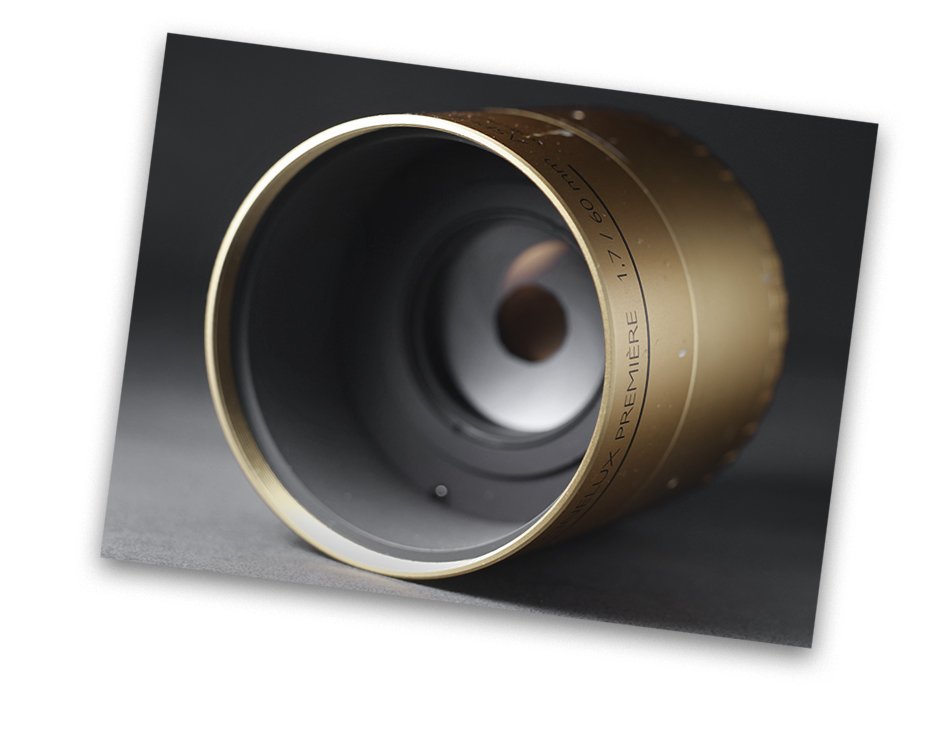

Finally in 2005 Schneider Kreuznach unveiled the Cinelux-Premiere f/1.7, a series of lenses which – while not among the fastest lenses ever – stands out because of its variable aperture – a fitting swan song before the death of analog and the birth of digital projection.

At present, digital projection lenses haven’t captured the imagination of digital shooters seeking adapted lenses. There are reasons for this: first, they were typically integrated in projectors using proprietary mounts – you can’t just pluck them out and fit them in standard clamp adaptors; second, the transition to digital at the turn of the millennium coincided with the final demise (after a long decline) of time-honoured American, European and Japanese makers; Third, commercial digital projection lenses are currently fearfully expensive – as indeed were the lenses above in their day. However the need for speed remains, and as digital projectors reach the end of their lifespans, and people begin to raid skips for optics culled from them, no doubt we will see pioneering adaptors deploying them as creatively as we now see analog-era optics being used.

There’s more…

While lenses intended for X-ray, TV-projection and similar applications come with their own restrictions and challenges in terms of adaption, there’s a good number of fast ones among them which might make the above list as well.

On his website, Espen Susort writes about the unique Astro Berlin Astro-Kino VII 100/1.4 and shares a view that – despite being marketed as a 16 mm projection lens – the lens was originally made for 35 mm projection. You can take a look at his writeup here >.

In the 1940s Taylor Hobson created a giant 310/1.5 lens for TV projection. I’ve not seen any attempt to adapt that hing however.

Angenieux created the massive TV-1 120/1.2 lens, but – as the name implies – it was also used for TV-projection and is thus not particularly well suited for photography. Toby Marshall has created a couple of interesting shots with it regardless.

Kollmorgen also created a similar lens, the 153/1.0 and it likely was used for a comparable purpose. There’s also no documentation about anyone adapting that unfortunately.

Zeiss created the giant R-Biotar 100/0.73 though not made for cine projection purposes, still an interesting lens and in some ways similar. Espen Susort shares some more information and wonderful results here.

However, here’s a word of caution: while many X-Ray or TV-projection lenses may seem like wonderful candidates for adaptation with their impressive specs, the vast majority of them are not suited for being used as taking lenses. Many of them won’t focus at distance or can damage your camera sensor because of their ultra-short focal-flange distance. Many are not corrected for color-photography and show a significant defects in that application, beyond the standard low-contrast “vintage look”. You may find this just what what you’re looking for – or not! Capitalising on the timeless appetite for speed, also beware bizarrely inflated pricing by at best opportunitistic (at worst unscrupulous) sellers making spurious connections to well known cine or taking lenses. Do your research before pulling the trigger.

Watch this space for a follow-up article discussing fast 16mm projection lenses . . . .

Big Thanks to…

Bosun Higgs for his great input on the topic, particularly UK-based lenses.

Espen Susort for showing some unique fast lenses on his site >

Toby Marshall for sharing his findings on various interesting fast projection lenses and modifications.